The United States boasts a vibrant architectural heritage, shaped by centuries of cultural, social, and environmental influences. Architectural genres in the US reflect the nation’s diverse history, from its early colonial settlements to its modern urban landscapes. Each genre carries distinct characteristics, responding to the needs, values, and innovations of its time. This article delves into the major architectural genres that have defined American buildings and spaces, exploring their origins, features, and lasting impact.

Top 10 Architectural Genres

Colonial Architecture: Foundations of a New World (1600s–1700s)

Colonial architecture emerged as European settlers adapted their building traditions to the American landscape. Influenced by English, Dutch, French, and Spanish styles, these structures prioritized durability and functionality to endure unfamiliar climates.

Origins and Context: Early colonists built with local materials, tailoring designs to regional conditions. English settlers in New England faced harsh winters, while Spanish settlers in the Southwest contended with arid heat.

Characteristics: Symmetrical layouts, steep gabled roofs, central chimneys, and small, multi-paned windows. English Colonial homes used wood clapboards, Dutch Colonial featured gambrel roofs, and Spanish Colonial relied on adobe with red-tiled roofs.

Cultural Significance: These buildings reflected settlers’ practical needs and cultural identities, laying the groundwork for America’s architectural evolution.

Notable Regions: New England, New York, Florida, and the Southwest.

Georgian Architecture: Classical Order and Elegance (1700s–Early 1800s)

Named after England’s King George, Georgian architecture brought classical symmetry to the colonies, signaling growing wealth and cultural refinement.

Origins and Context: Inspired by Renaissance interpretations of Greek and Roman architecture, Georgian style flourished in prosperous colonial cities and continued post-independence.

Characteristics: Balanced facades, brick construction, decorative crown moldings, and Palladian windows. Interiors often featured ornate plasterwork and grand staircases.

Cultural Significance: Georgian architecture embodied the colonies’ aspirations for sophistication, with public buildings and elite homes projecting stability.

Notable Regions: Virginia, Massachusetts, and urban centers like Philadelphia.

Federal Architecture: A Young Nation’s Identity (1780s–1830s)

Federal architecture, also called Adam style, emerged after the American Revolution, blending Georgian restraint with delicate neoclassical details.

Origins and Context: Influenced by British architects like Robert Adam, this genre reflected the new nation’s desire for a distinct, refined aesthetic.

Characteristics: Lightweight ornamentation, elliptical arches, fanlights above doors, and pastel interiors. Structures maintained symmetry but felt less heavy than Georgian designs.

Cultural Significance: Federal architecture symbolized America’s independence and optimism, seen in government buildings and urban residences.

Notable Regions: Boston, Washington, D.C., and coastal cities.

Greek Revival: Democratic Ideals in Stone (1820s–1860s)

Greek Revival celebrated the democratic ideals of ancient Greece, aligning with America’s growing national pride.

Origins and Context: Inspired by archaeological discoveries in Greece, this genre gained popularity for public buildings and homes during the early 19th century.

Characteristics: White-painted exteriors, bold columns, pedimented gables, and temple-like forms. Interiors featured simple, classical detailing.

Cultural Significance: The style’s association with democracy made it ideal for courthouses, banks, and plantation houses, reinforcing civic identity.

Notable Regions: The South, Midwest, and Northeast.

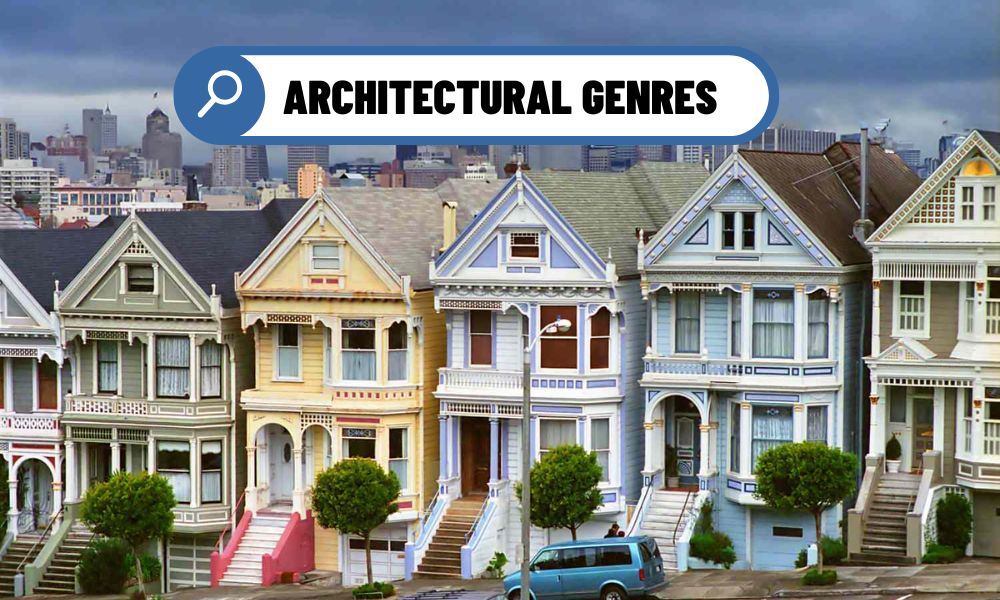

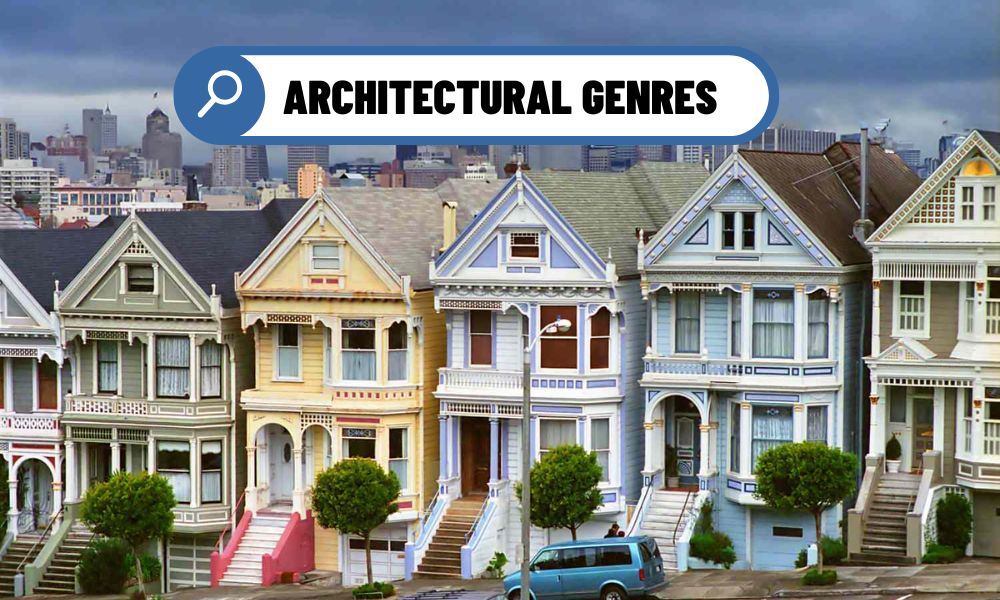

Victorian Architecture: Ornate Eclecticism (1830s–1900)

The Victorian era embraced diversity and ornamentation, driven by industrialization and romantic ideals.

Origins and Context: The Industrial Revolution enabled mass production of decorative elements, while global trade introduced exotic influences.

Characteristics: Asymmetrical designs, intricate woodwork, stained glass, and vibrant colors. Sub-styles included Italianate (low-pitched roofs, brackets), Queen Anne (turrets, wraparound porches), and Gothic Revival (pointed arches, tracery).

Cultural Significance: Victorian architecture reflected individualism and prosperity, with homes and public buildings showcasing personal and civic pride.

Notable Regions: San Francisco, New Orleans, and growing industrial cities.

Arts and Crafts (Craftsman): Simplicity and Nature (1890s–1930s)

The Arts and Crafts movement, including the Craftsman style, rejected Victorian excess, emphasizing handmade quality and natural harmony.

Origins and Context: Inspired by British reformers like William Morris, this genre gained traction in America as a response to industrialization’s dehumanizing effects.

Characteristics: Low-pitched roofs, exposed beams, wide porches with tapered columns, and natural materials like wood and stone. Interiors featured built-in furniture and earthy tones.

Cultural Significance: Craftsman homes prioritized affordability and authenticity, appealing to the middle class and promoting a lifestyle connected to nature.

Notable Regions: California, the Midwest, and Pacific Northwest.

Prairie School: Organic Integration (1890s–1920s)

Pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright, the Prairie School sought to create an uniquely American architecture rooted in the Midwest’s landscapes.

Origins and Context: Emerging in Chicago, this genre emphasized horizontal lines to echo the flat prairies, rejecting European Revivalism.

Characteristics: Low, horizontal profiles, overhanging eaves, open floor plans, and extensive use of glass to connect interiors with nature.

Cultural Significance: Prairie School introduced organic architecture, influencing modern design with its focus on environment and functionality.

Notable Regions: Illinois, Wisconsin, and the Midwest.

Modern Architecture: Form Follows Function (1930s–1960s)

Modern architecture embraced minimalism, technology, and universal design principles, reshaping American cities and suburbs.

Origins and Context: Influenced by European Bauhaus and architects like Le Corbusier, modernism responded to industrialization and urbanization.

Characteristics: Flat roofs, open floor plans, large glass windows, and materials like steel and concrete. Mid-Century Modern, a subset, added playful curves and vibrant colors.

Cultural Significance: Modernism reflected post-war optimism and efficiency, shaping suburban homes and urban skyscrapers.

Notable Regions: California, New York, and nationwide suburbs.

Postmodern Architecture: Playful Rebellion (1970s–1990s)

Postmodernism challenged modernism’s austerity, reintroducing color, ornament, and historical references with a sense of irony.

Origins and Context: Emerging as a critique of modernist uniformity, architects like Robert Venturi embraced complexity and contradiction.

Characteristics: Eclectic forms, bold colors, asymmetrical designs, and playful nods to classical or regional motifs.

Cultural Significance: Postmodernism allowed architects to experiment freely, creating iconic buildings that blended humor with sophistication.

Notable Regions: Urban centers like New York and Miami.

Contemporary Architecture: Sustainability and Innovation (1990s–Present)

Contemporary architecture prioritizes flexibility, environmental consciousness, and technological integration.

Origins and Context: Driven by climate change and digital advancements, this genre adapts to modern lifestyles and global challenges.

Characteristics: Clean lines, sustainable materials, green roofs, and smart home systems. Designs often blend minimalist aesthetics with eco-friendly functionality.

Cultural Significance: Contemporary architecture reflects a commitment to sustainability and adaptability, addressing urban density and environmental concerns.

Notable Regions: Nationwide, especially in tech hubs and eco-conscious cities.

Regional Influences: Shaping Local Identity

American architectural genres are deeply tied to geography. Northeastern colonial homes endure cold winters with sturdy brick. Southern plantation houses feature verandas for ventilation, while Southwestern adobe reflects desert climates. Midwestern Prairie homes mimic flat horizons, and Western modern designs embrace open landscapes, blending indoor and outdoor living.

A Tapestry of Time and Place

The architectural genres of the United States form a rich mosaic, each reflecting the era, values, and landscapes from which it sprang. From the pragmatic simplicity of colonial homes to the eco-conscious innovation of contemporary designs, these genres tell a story of adaptation and creativity. As America continues to evolve, its architecture will remain a dynamic expression of its diverse identity, balancing tradition with progress.